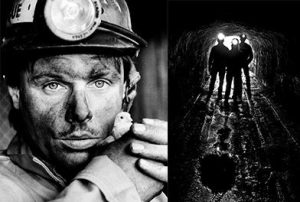

Jews are using the phrase “we are the canary in the coal mine” as a warning that anti-Semitism signals growing hatred of all groups in our nation. This idea is profoundly flawed, ironically counterproductive, and requires immediate redress.

anti-Semitism signals growing hatred of all groups in our nation. This idea is profoundly flawed, ironically counterproductive, and requires immediate redress.

The phrase is a desperate appeal to others that they must fight anti-Semitism as it inevitably will lead to hatred against them—that tactic won’t work. People will stand against anti-Semitism because it is wrong. And if they can rationalize anti-Semitism, they won’t care about Jews, canaries, or anyone else. Besides, there is another group that already experiences an institutional brand of hatred: black people and others of color.

People of color have been experiencing hatred and systemic racism for as long as any of us have come to these shores. When we think of Jews as the ones on the front line, we negate the experience of the black community. That is egotistical and shameful and ironically belies the idea embodied in the Canary Phrase. We should be aware of this hatred and align with those others who experience it.

I am not a canary, and I am not in a coal mine. Despite the alarming sharp increase in public displays of anti-Semitism, we live well, thoroughly enjoying so many blessings of this place. We have the power and the means to defend ourselves. And we are. Others do not, and we must help them.

Let us stand against hatred in all its forms besides every one of goodwill. We denounce hatred of any group and work together to fight it on the streets, in the courts, and our hearts. So our country may live up to its aspirations.

We are not birds; we are American Jews standing tall for the values we believe in, and together, we will prevail.