One Day

Something amazing happened in Haifa a couple of years ago. Three thousand people gathered to sing a song- Matisyahu’s song One Day. Words in Hebrew, Arabic, and English combined into a single voice of love and hope.

Enjoy, Shabbat Shalom!

You can make a difference! Go to World Central Kitchen to learn how to advocate in Congress and to support chef Jose Andres’ incredible work at World Central Kitchen

This stunning rendition of Batya Levine’s “We Rise” comes to us through the artistry of Cantor Harold Messinger, of Beth Am Israel Penn Valley, in collaboration with the talented James Pollard Jr., of Zion Baptist Church of Ardmore.

This Juneteenth, we commemorate and wish Shabbat Shalom!

June 19th is celebrated in American history as the date when the slaves were freed (it actually was the day when Union Troops entered Texas to enforce the final ending of slavery on June 19, 1865, three years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of Sept 22, 1862). Juneteenth, as it is known, remains an aspiration. Today, in this special moment in time we find so much of America is still unfulfilled; Ideals yet to be achieved, dreams yet to realized. America was the Promised Land for so many, but the promise is a work in progress, a distant goal for far too many.

June 19th is celebrated in American history as the date when the slaves were freed (it actually was the day when Union Troops entered Texas to enforce the final ending of slavery on June 19, 1865, three years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of Sept 22, 1862). Juneteenth, as it is known, remains an aspiration. Today, in this special moment in time we find so much of America is still unfulfilled; Ideals yet to be achieved, dreams yet to realized. America was the Promised Land for so many, but the promise is a work in progress, a distant goal for far too many.

On this Juneteenth let us affirm our commitment to make this special place one that extends ideals of equal justice, liberty, and equality to everyone. It is a long road ahead, but it is a journey worth traveling.

Find a group that promotes our sacred values such as the ADL, the ACLU, the Innocence Project, Repairers of the Breach, and support them. Learn how to help create the changes to make our society juster and fairer for all. Celebrate Freedom on Juneteenth and every day thereafter.

Behar-Bechukotai

Have you ever taken a vacation?

Usually, it is for one of two reasons:

To see or experience something new, or to Rest and relax (and of course some of us combine these). Both are ways to recharge to have a reset, time away from the normal and challenging tasks of work to engage in shavat v’yinafash, resting and refreshing both the body and the soul.

This week׳s Torah Portion Parsha Behar-Bechukotai talks about a reset- The Shmita -a reset of the land. Every seven years we are supposed to stop tilling the soil to let the fields recharge and all people regardless of stature; resident, worker, and slave alike, even the animals, get to partake equally in what is there.

We let things lie dormant so they can be rejuvenated.

The land is recharged and also not uncoincidentally those who do the hard physical labor of farming are given a respite as well. We do this for seven cycles of seven years and then in the 50th year is the Jubilee. “And you shall sanctify the fiftieth year, and proclaim freedom for slaves throughout the land for all who live on it. It shall be a Jubilee for you, and you shall return each man to his property, and you shall return each man to his family.”(Lev 25:10)

What might we learn from such a giant reset?

Our tradition recognizes that there are imbalances in the system- imbalances inherent in all systems. Some people are more successful in acquiring things, in working skillfully or even artfully, some possess better business acumen, some are particularly adept in choosing the right parents perhaps. And then, there are those not so skilled. The Talmud extensively discusses the issue that “Batar Anya Azla Aniyuta,” or “poverty follows the poor” or that Poverty actually increases from being impoverished.

All societies naturally tend towards these proclivities, and it is up to us, those who can make a difference, to make a change. To reset society to align with our values and principles. Another example of such a reset is commemorated at this time in our calendar.

As we mark the 34th day of our trek to Sinai the story of Shimon Bar Yochai is also worth noting. A disciple of Rabbi Akiva, he and his son, Eleazar, fled to escape the Romans, living in a cave for 12 years. He emerged but instead of re-joining his community, he was disgusted by a perceived lack of piety by the people. Shimon’s eyes burned everything they saw to a cinder, field and man, alike. God’s messenger, The Bat Kol, sent him back to the cave for another year and he emerged an enlightened man dedicated to righteous living and scholarship, redeeming Tiberias and possibly laying the groundwork for writing the seminal book of Jewish Mysticism, the Zohar.

This is the charge of this week’s Parsha- for each of us individually to rededicate ourselves to serving the needs of our people compassionately and deliberately, fully committed to the sacred cause of living Jewishly if we are willing to take up the challenge.

When this health emergency is past, will you emerge hardened from the cave? Or will you emerge from this quarantine open and deeper in touch with the values that are there to guide you? Or, will you figuratively burn what you see to the ground by turning a blind eye towards the deep injustices and needs that exist, or instead, will you choose to engage in pursuing righteousness and Jewish values, treating the people with Tzedek and compassion?

Which path will you choose?

May you choose to walk the Jewish path

Cain Yehi Ratzon,

It is me sporting an American Red Cross lapel pin saying, I am a proud volunteer with a great organization and I am asking you to join me. The American Red Cross is a wonderful humanitarian organization devoted to helping people in need during times of crisis.

I am part of the Disaster Spiritual Care team. I was deployed to help the people of Pittsburgh in the wake of the shooting. Every time there is a need, from house fire to conflagration, from minor flooding to hurricanes, from natural to man-made disasters, the American Red Cross is there. And we need more help.

As a volunteer, you will be trained to share in the amazing work we do. It is an incredible way to give back to your home community, in my case the Jewish community, or wherever the need might take you. It is a wonderful and rewarding experience. Please join me. Go online at your local American Red Cross chapter to begin the process. JOIN US!

#4 What do we do now- Be Kind

We come to the Third part of Hillel’s quote: If not now, When? The answer is NOW.

I have refrained from speaking directly about Charlottesville with you thus far.

I am sure that the public display of hate deeply pained you.

The horrible chants, torch-lit marching, gun-toting thugs,

40 Jews inside Congregation Beth Israel that evening,

spiriting their Torahs out the back door, expecting the Temple to be burned, it sickens me.

The Nazi march was vile and despicable behavior by people who live on the fringes of our society,

a group that trucks in hatred,

truly disenfranchised miscreants who crawled out from the dark underbelly of this great nation

and are mired in their own bizarre fantasies of violence and white supremacy.

I am very angry and deeply saddened by this horrific display.

And I am equally appalled by the lack of moral leadership on this and all issues at the highest levels in our land.

However, I am not fearful.

And in response to the horrors of Charlottesville

I have a one-word reply:

Houston.

Charlottesville and many other places make it clear we have a long way to go in the battle for life, liberty, and equal justice for all.

Again I say Houston. For there in Houston, there is hope.

In response to the devastating Hurricane Harvey that dumped floodwaters of biblical proportions on the region,

the very best of humanity showed up to the rescue.

There were only two groups in the city:

The rescuers and those in need of rescue.

Race, religion, color, creed, age, sex, gender identification, political affiliation, economic class, social class-

Nothing mattered except the need to save lives of people.

The Cajun Navy spontaneously appeared, people helped people, human chains literally reaching out into the floodwaters,

holding tight to each other

so that another life could be saved from the torrents of water. Everyone was on both ends of that lifeline.

In losing everything, the people of Houston found something truly precious, their humanity.

My response to the horror of Charlottesville is the beauty of Houston.

We seem to be at our best in the aftermath of a calamity.

Houston, Sandyhook, 9/11- these are only a few catastrophes to which we have risen up as a people,

United in bonds of love and fellowship.

Why must we reserve our best in response to tragedy?

This Yom Kippur, I suggest we preemptively deploy our best behavior in our everyday lives.

Let us shine light into the darkness

and illumine a path that leads out of the narrow places,

the Mitzrayim- the Egypt- those spaces both literal and figurative that both confine and oppress us.

Let us join together doing acts of loving-kindness.

Let us not sit helplessly and lament the world we long for.

Let us reach out to one another and build the world that should be. Let the humanity of Houston be our inspiration.

Together let us march forward

carrying love in our hearts and good deeds in our arms.

We have come to the proverbial edge of the Red Sea,

yet one more time in our history. Let us cross over together.

(And if I sound a bit like a Southern Baptist preacher, I can only say, Thanks, Grandma.)

How do we do this?

For you may say, I am only a single individual-

what effect can I possibly have?

I recall the story told of Mother Theresa,

that saint who tended the poorest of the poor in India.

A cynic asked her how she intended to feed the overwhelming masses who were hungry- she responded simply,

One Mouth at a Time.

And that is how we do it.

Each of us has the power to effect change.

The V’ahavta prayer says VeLo Taturu.

Never underestimate the power to make a difference- each of us.

It is about meeting people, one person at a time.

It is about individuals building relationships with one another

and building these connections into bigger connections,

building a community with shared values and purpose.

And it all starts with one simple idea: You.

Rabbi Hillel says in Pirkei Avot,

“In a place where there are no men, strive to be a man.”

As Jeffrey Goldberg of the Atlantic insightfully translates,

it means to be a mature, courageous human being;

it also means to be a mensch. So I sum it up and say simply to you: Be Kind.

In an age and culture where we have become coarse and combative,

BE KIND.

In a world filled with overwhelming loneliness and alienation,

BE KIND.

In a world quick to cynically chastise and separate with fractiousness and divisiveness,

BE KIND.

Hillel condensed all Torah to this:

“What is hateful to you, do not do to another.”

BE KIND. This as our call to action.

Start with yourself.

Let us free ourselves from the shackles of guilt and sin keeping us mired in the past.

Learn from it to live next year better.

Be kind and forgiving of your self. Starting now.

Promise yourself to engage.

Jews are taught to awake with the words “I am Thankful.”

“Modeh Ani Lifanecha, Elohai Nishama Shenatati bi tihora hi.” ‘Thank you God for restoring my pure soul.”

What a beautiful intention to start the day.

A fresh slate, built on gratitude for our blessings

and hopeful for the possibilities that await us.

Use the day to engage in the things that motivate you- your Why. Actively support something you believe in,

a philanthropy or a cause,

be part of something greater than yourself.

End your day with a bedtime Shema- prayer.

Go to sleep knowing

you are in the sheltering arms of the One who loves and protects you.

Nurture your relationships.

Be compassionate and forgiving; for they too are as flawed, seeking wholeness and love.

BE KIND.

Find your community and

BE KIND.

We need a caring community to support and comfort us

During times of celebration and sorrow.

Temple Micah is an extraordinary community to find people with shared values.

And together we can make a difference

rising up our voices as one,

speaking with more power than one alone to affect greater change. Give to the food bank,

give to help the suffering victims on Puerto Rico.

BE KIND.

Our greater communities, both our nation and the world,

need people to champion our values now more than ever.

Your voice, your time and your money are all necessary

to champion the things you believe in.

There is no shortage of need, and we cannot be silent.

“Kol Arevim Zeh BaZeh.”

All Israel is responsible for each other.

Whether you see Israel literally or metaphorically,

you can make a difference in

the genocide of the Rohingya, happening as we speak,

climate change, Israel, healthcare, the political debate both national and local.

These issues are our issues.

Find the one that resonates with your and pursue it.

We need to build a better world.

I believe it can happen.

But only if we are willing to roll up our sleeves and do the work necessary,

for it cannot happen on its own.

As it says in Psalm 89 verses 3,

Olam Chesed Yibaneh. “We will build this world with love.”

Jewish Love is not romantic love.

We learn Jewish love in the Shema and V’ahavta prayer.

Love is an active verb.

Jewish love is not a state of being, it is a state of doing.

The prayer instructs us to Love God by living the commandments, teaching them to our children

and fully embracing them in all of our thoughts and actions.

Jewish wisdom sees the Heart as the guide to emotion and action. I am the change I want to see.

This is the empowering message of the Torah.

It implores us to embrace that

only through our own action will we begin to build the world that should be.

The people of our nation have always had to fight for the values we hold dear;

from the moment we first expressed them through the present day. This amazing country of ours is both resilient and great.

But we remain a work in progress with a long way to go before all of her children will enjoy the aspirations of our foundational documents, including the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights and Emma Lazarus’s poem on the Statue of Liberty.

Life, liberty, and equal justice for all remain the promise we still strive to achieve.

This promise is the beacon of light shining from on top of the hill to the other nations of the world.

We will build this nation on love.

Olam Chesed Yibaneh. We will build this world on love.

As we move toward the end of our prayers today

we will hear that the gates are closing and also

that the gates of repentance are never closed.

These two seemingly contradicting ideas both live in our texts.

I believe that with Ne’ilah, our closing prayers,

the liturgists are exhorting us to act.

It is the urgency of now. We cannot wait.

The prophetic tradition that is ours,

The fragility of life that makes each day a gift-

they combine to say “don’t wait another minute.”

So here is this sacred space, as we conclude our services this day,

I encourage everyone here to smile at one another,

kiss and embrace your loved ones,

and kiss and embrace whoever is near you.

This is the start of something new.

We will build this world with love.

G’mar Tov- May you be sealed for Good

Olam Chesed Yibaneh (sing)

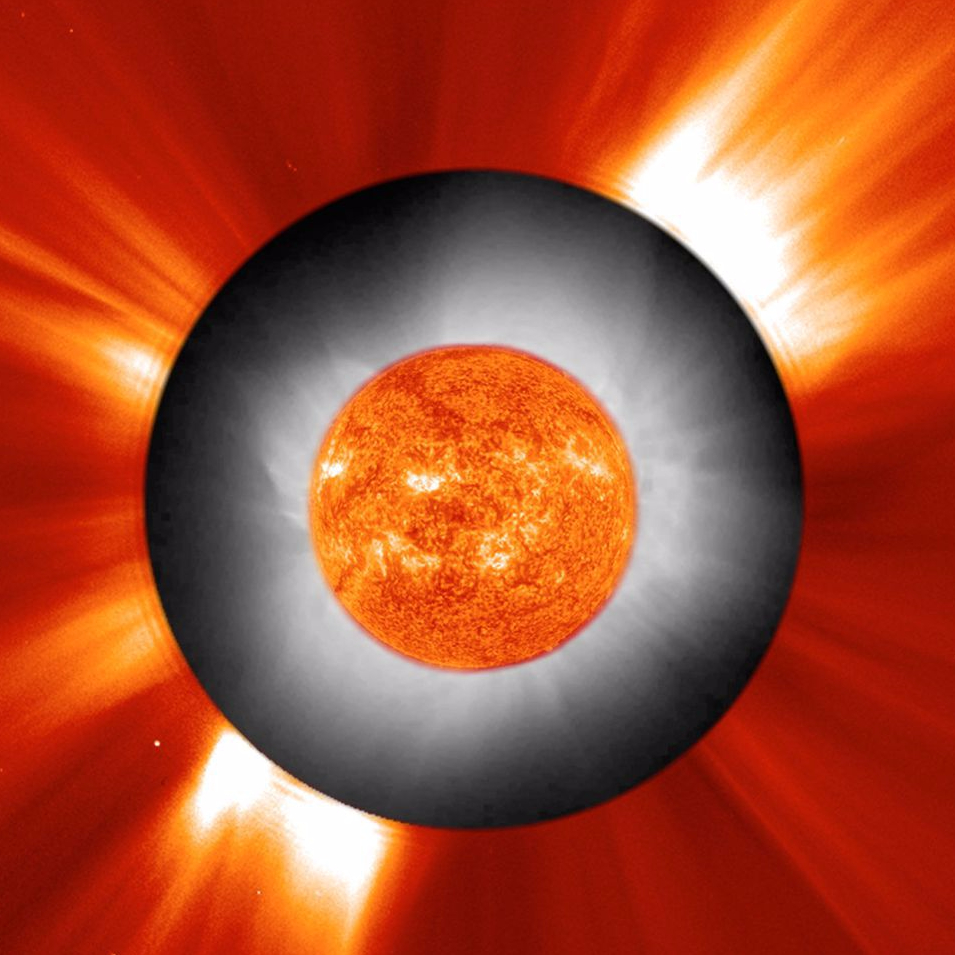

Like most things meaning is often something we ascribe rather than something intrinsic. An eclipse is a fact of the physical world based on orbiting bodies and the shadows they cast when sun moon and earth interact. They are knowable and predictable.

Like most things meaning is often something we ascribe rather than something intrinsic. An eclipse is a fact of the physical world based on orbiting bodies and the shadows they cast when sun moon and earth interact. They are knowable and predictable.

Our tradition has suggested that an eclipse portends an unfavorable time for the world. A lunar eclipse was a bad omen for the Jewish people in particular, perhaps because of our connection to the lunar cycles in our calendar. I particularly like the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s z”l understanding that this is an opportunity to increase prayer and introspection. I do not know whether an eclipse would prompt certain bad behaviors to come out. This idea seems to lapse into the realm of the bubbe meise or superstition. But anything that makes us pause and consider things a bit more deeply about our circumstances is worthwhile. We have portents and signs all around us if only we would recognize them. Often we do not and even more rarely do we use it as a call to action.

I recall my first solar eclipse. It happened when I was a child living in the “holy city” of Monsey, NY. My father fashioned a special viewer so I could watch the progression. It was essentially little more than a cardboard box with a peephole. I was transfixed as the eclipse took place. The silhouette of the sun showed it being obscured and the sky turned a strange hue. I vividly recall being cautioned by my dad not to look at the sun because I would go blind. But I could not resist at least a quick glance skyward to see this extraordinary event directly and so I looked. Thankfully my sight was preserved, although at the time I was concerned. My recollections, however, are of the silhouette crossing that white piece of paper in the cardboard box my dad made for me.

What we do with this amazing event is, like so many things, up to us. I suggest that for those who can see it, watch the eclipse with a sense of wonderment and awe for the extraordinary world in which we live, contemplate your place in it, and act.

*I thank Chabad.org for sharing thoughts of the Rebbe.