This evening is Shabbat Shuva, the Shabbat between Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur. May your High Holidays be meaningful and 5778 be a year of health and blessings.

L’ShanahTovau’metukah!

Shabbat Shalom

This evening is Shabbat Shuva, the Shabbat between Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur. May your High Holidays be meaningful and 5778 be a year of health and blessings.

L’ShanahTovau’metukah!

Shabbat Shalom

Leon Bridges song River has been in my head for most of Elul as I try to prepare myself for the High Holidays. It seems a perfect song for Tashlich. I hope you enjoy it and find it deeply moving too.

Wishing everyone a Happy Healthy 5778, may it be a year filled with blessings.

L’Shana Tova!

As we progress through the month of Elul towards the High Holidays, take a moment to listen to this wonderful duet. Naftali Kalfa and Gad Elbaz sing of return to the Almighty in Teshuva. A beautiful song to start Shabbat.

Shabbat Shalom!

When a couple marries, is the ceremony one of Solemnization or Sanctification? This is an important distinction to understand for couples getting married and for those of us doing the officiating. When an officiant solemnizes a wedding he/she duly performs a formal marriage ceremony. When an officiant sanctifies something, that something is consecrated, set apart and declared holy, or made legitimate by a binding religious sanction. It is important to see that one can perform a legitimate ceremony (solemnize) without adding the consecration. And in point of fact, officiants are often called upon to do the one without the other.

When a couple marries, is the ceremony one of Solemnization or Sanctification? This is an important distinction to understand for couples getting married and for those of us doing the officiating. When an officiant solemnizes a wedding he/she duly performs a formal marriage ceremony. When an officiant sanctifies something, that something is consecrated, set apart and declared holy, or made legitimate by a binding religious sanction. It is important to see that one can perform a legitimate ceremony (solemnize) without adding the consecration. And in point of fact, officiants are often called upon to do the one without the other.

My role as a rabbi requires that I be committed to doing both. But that does not mean that a different officiant, a layperson, for example, cannot also incorporate the holy into the ceremony. For all of us, it requires deliberate forethought to solemnize and sanctify a wedding.

If someone asks me to perform a service that uses Jewish ritual as a perfunctory overlay, I believe that still falls under the auspices of solemnized but not sanctified (and something I am uncomfortable doing). It is only when the ritual is embraced as part of the meaning making process that we can elevate the ceremony to be one of consecration.

I have long thought about this issue as couples approach me regularly. I need the couple to make a commitment to a Jewish family and future, as well as a ceremony that resonates with the couple. Every couple I work with therefore is required to invest time and effort to understanding the rituals they will include and exclude from their ceremony in addition to having the important conversations with each other to discover what each of them understands as a Jewish family and future. I serve as the lamplighter on this journey.

A young woman shared that she was asked to officiate at her sister’s wedding. The couple said it was because the sister knew them well. The couple is in love but neither is religiously affiliated or active. Given their lack of attachment to Judaism, it is likely a ceremony that I would not do. But this anecdote points to a trend towards serious, but non-religious union. I am sure that this young woman will do her utmost to provide a meaningful ceremony. However, she will need to invest much effort in order to sanctify and solemnize her sister’s wedding (I am confident that she will, and I stand ready to help her). I wonder if the fee-for-service or mail-order ministers would do justice on behalf of the couples they ostensibly serve.

Sanctification should be an important consideration for every couple seeking a meaningful ceremony. And it needs to be an issue that every officiant honestly confronts.

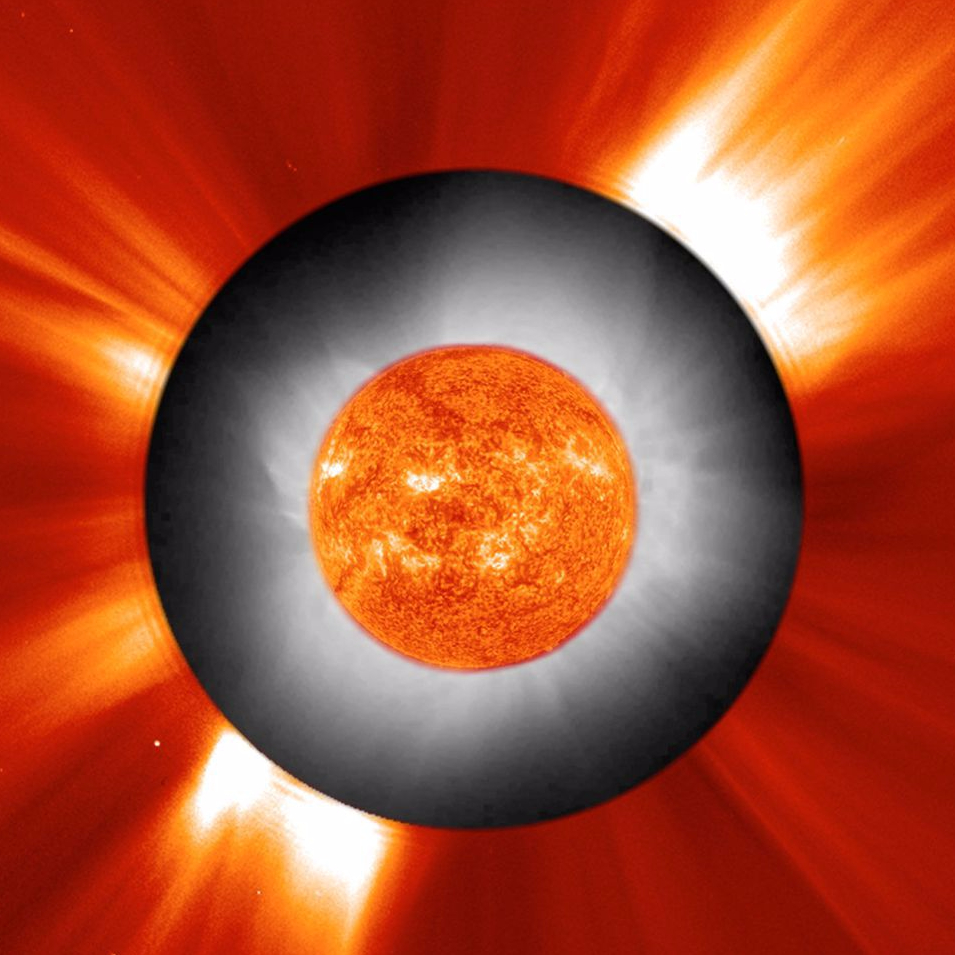

Like most things meaning is often something we ascribe rather than something intrinsic. An eclipse is a fact of the physical world based on orbiting bodies and the shadows they cast when sun moon and earth interact. They are knowable and predictable.

Like most things meaning is often something we ascribe rather than something intrinsic. An eclipse is a fact of the physical world based on orbiting bodies and the shadows they cast when sun moon and earth interact. They are knowable and predictable.

Our tradition has suggested that an eclipse portends an unfavorable time for the world. A lunar eclipse was a bad omen for the Jewish people in particular, perhaps because of our connection to the lunar cycles in our calendar. I particularly like the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s z”l understanding that this is an opportunity to increase prayer and introspection. I do not know whether an eclipse would prompt certain bad behaviors to come out. This idea seems to lapse into the realm of the bubbe meise or superstition. But anything that makes us pause and consider things a bit more deeply about our circumstances is worthwhile. We have portents and signs all around us if only we would recognize them. Often we do not and even more rarely do we use it as a call to action.

I recall my first solar eclipse. It happened when I was a child living in the “holy city” of Monsey, NY. My father fashioned a special viewer so I could watch the progression. It was essentially little more than a cardboard box with a peephole. I was transfixed as the eclipse took place. The silhouette of the sun showed it being obscured and the sky turned a strange hue. I vividly recall being cautioned by my dad not to look at the sun because I would go blind. But I could not resist at least a quick glance skyward to see this extraordinary event directly and so I looked. Thankfully my sight was preserved, although at the time I was concerned. My recollections, however, are of the silhouette crossing that white piece of paper in the cardboard box my dad made for me.

What we do with this amazing event is, like so many things, up to us. I suggest that for those who can see it, watch the eclipse with a sense of wonderment and awe for the extraordinary world in which we live, contemplate your place in it, and act.

*I thank Chabad.org for sharing thoughts of the Rebbe.

I am excited to announce the launch of Conversations for Life and Legacy™.

I am excited to announce the launch of Conversations for Life and Legacy™.

Conversations for Life and Legacy™ is a whole new approach to sharing our wisdom, making meaning in our lives, and connecting beyond ourselves drawing upon the insights of Jewish tradition and text.

Conversations for Life and Legacy™ goes far beyond an Ethical Will to share our sacred stories in unique new ways. Among the particular innovations are using a rabbi trained in chaplaincy to guide the interview and capturing it all on video.

Please look at our new website: www.ConversationsForLifeAndLegacy.com to explore this new approach; see what it can mean to you and how it can be brought to your community.

Today we also launch a Facebook page: ConversationsForLifeAndLegacy and we will be on Twitter as well @rabbidavidlevincll.

It’s time to have the Conversations of your Life!

Conversations for Life and Legacy™

www.ConversationsForLifeAndLegacy.com

I just received my new passport. The old one was expiring and I dutifully followed the instructions, got a new picture, completed the DS-82 form, mailed it and in the mail was the new passport. But I miss the old one.

I got the old one as I prepared to enter a new phase of my life, leaving a 30-year career in business to become a rabbi. Looking back, it has been a fascinating decade chronicled by this small blue book. Stamps representing my trips to and from Israel as a rabbinical student, my trips through the Former Soviet Union celebrating Pesach in Moscow and cities in Siberia, my honeymoon in Italy with Naomi as a newlywed, the trips to Israel as a rabbi, and a wedding in the Dominican Republic, were all documented by this small blue book with worn edges. Each page is a reminder of a very special experience.

I remember the process of obtaining it, completing other forms and taking other pictures that showed a younger version of me with more hair on top of my head and less gray on the face. The book was empty and new. It was literally and figuratively my passport to my future. Each of those stamps represented an amazing journey. Each was memorialized in that precious little book that I scrupulously guarded but whose inside page I copied just in case my best-laid plans to protect it was subverted.

Extraordinary memories of extraordinary experiences are evidenced in my old passport. It serves as a reminder that we continue to grow and each passing day is another page in our life journey. I reflect back on them and see something I learned and perhaps can share with others. My life is enriched and so too is my capacity to teach.

So now I have the new passport. The picture inside is of an older, current version of me. The pages are clean and new. I can only wonder about the adventures and how those pages might be filled over the next decade. The fresh pages beckon with anticipation and promise. I can only hope that when it is time to replace this contemporary passport, it too will worn and maybe tattered, filled with visas and stamps of exciting travels evoking meaningful memories declaring that my continuing life journey remains a rich experience of growth and sharing.

At Shavuot, how we receive the gift of Torah is one of the great questions posed. I found a path towards understanding in a passage of the Talmud.

One is really two and two is really four. This is not a set of alternative facts but an insight from the Talmud (BT Shabbat 2a) about the nature of things. Shavuot is the time of the giving of Torah. But in any transaction there are two components, giving and receiving; one is really two. But it doesn’t stop there.

Both giving and receiving are either active or passive. In giving, we can thrust it towards another actively or we can be passive and open our hands for the other to take it. Similarly, in receiving, we can actively take the gift with eagerness and enthusiasm, or we can open our hands to passively receive the gift that is to be bestowed upon us. Two is really four.

So at this time of matan haTorah, the giving of the Torah, how do we receive it? Our tradition focuses that this is a gift from God to us and it is about the giving. The Eternal gave it once but we are always receiving Torah. And although we think of ourselves as all being at Sinai in this incredible moment, each generation comes to Torah to take it as their own. It is entirely up to us to accept it passively or embrace it actively.

How will we come to Torah?

Will you grab the Torah with gusto or just accept it. Is it truly a gift a living thing that brings meaning to us, something extraordinary to be treasured, loved, and lived; or is it some musty manuscript kept safely away in an Ark in a place we rarely visit if ever? The choice is ours, collectively and individually.

Perhaps it is this distinction in the way we receive this gift that helped God understand that the generation that received Torah was not the generation ready to enter the Promised Land. For the way we receive a gift can affect how the giver gives the next gift, which builds on the first. If we receive it enthusiastically and with gratitude, the gift giver might be more excited to bestow the next gift. And if we receive it passively perhaps the giver might consider whether, in fact, the recipient was ready for it or for the next gift.

This brings to mind the phrase mitzvah goreret mitzvah (Pirkei Avot 4:2) a good deed encourages more good deeds. So at this special time and place, are we able to exclaim a special Shehecheyanu, enthusiastically offering gratitude to God for this amazing gift of Torah, and use it to live our lives fully and with meaning, and preparing ourselves for God’s next gift?

I need to talk about the current ad Heineken has produced and also the talk about the talk surrounding the current ad.

For starters, we all need to acknowledge the ad is designed to promote Heineken beer. With this disclaimer, we can proceed. Bottom line, I found the ad had a positive message (beyond Heineken is a good beer to drink with someone). I believe the message was that people operate according to preconceptions whether or not they are fully informed or people hold opinions that keep them from hearing another viewpoint, but it does not have to be so.

The ad was a message about building bridges across those divides, seeing that the other is not merely stupid or a threat, or perhaps something even worse. We can find ways to connect ways to create relationships where they did not exist before; we can find that despite the things that differentiate, our common humanity can be something that brings us together.

The ad is precisely that, a four-minute frame into which the message of building bridges and the selling a product are interwoven. It is neither Shakespeare nor the Bible; although interesting, it is not the best of plots, or cinematic artistry, or even acting. But it is an important message none-the-less, one deserving of notice and embrace, not ridicule or cynicism.

I am struck that because I hold this opinion, some call me out as stupid for liking the ad and even stupider for not knowing how stupid I really am. People are reacting in a way that feels extremely condescending, or just smug, contemptuous of anyone who does not have the incisive clarity that this dangerous insidious ad requires.

The ad can be scrutinized and might actually be a starting point for some of the serious conversations we need to have, including what the ad omitted, the subtle prejudices it contained, what are the important issues dividing us, etc. But a conversation is hard to have when only one viewpoint is acceptable. It seems like some of the people so vocal in criticizing the ad would have been good “before” characters for the ad. Consider that as a working premise, we share our common humanity. Then over a drink, let’s sit together to talk and listen.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wYXw4K0A3g&t=12s

Our world seems to be in a particularly harsh place. On all fronts we seem to be ailing. People seem unable to talk with one another; our government and institutions are unresponsive to our needs; countries withdrawing from one another, many spiraling into brutal regimes. Anger, fear, and frustration divide us rather than hope guiding and uniting us. This is the backdrop to the double portion of Tazria/Metsora (Leviticus 12; 1-13:59, Leviticus 14:1-15:33), which interestingly addresses these very issues.

These Parshiot contain peculiar rituals that are actually timely messages. The ailments that afflict us are more than skin deep according to the Torah, indicating perhaps some spiritual or emotional sickness perhaps that causes the infirmed to be separated from the community. Because these ailments can infect bodies, clothes and even buildings we recognize that there is something more here than meets they eye. It runs deeper and we are compelled to question what might the Torah be cautioning us about. Torah’s message rarely stops at the edge of The Land so we can engage what these portions say about us. But first, let us examine the Parsha a bit closer.

Tazria continues the conversation about ritual impurity from the previous chapter, Shemini. The Parsha moves into the conversation surrounding Tzaraat, an affliction affecting people. It is often referred to as leprosy because it manifests itself as scaly white patches, but more interesting is the decision to bring in the Priest.

The Priest, instead of a doctor, views the afflicted person to decide if indeed this is Tzaraat. The priest instead of the doctor raises our collective eyebrows. We are not the first to grapple with the texts here. Two of our classic commentators, Rashi and Abarbanel, wonder about this too. Rashi hones in on the phrase that notes the Priest is called when the white patch seems to go deeper than the skin of the afflicted person’s body. Arbarbanel focuses in on the idea that the priest is called instead of a medical Specialist to provide treatment for the individual.

We know that medical treatment options were available. Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans practiced sophisticated medicine. In Exodus and 2Kings Abarbanel notes the use of medical treatments. Our texts speak of something besides some physical problem.

Our tradition has seen afflictions as a punishment for sin against God. Nachmanides says the Divine Spirit keeps bodies, clothes, and homes in good appearance. But when one of them sins, ugliness appears on his flesh, clothes or his house. Later, the text tells us that if the affliction reappears, the clothing is burned and houses were taken down. Sforno, another commentator, suggests that perhaps the seven-day process of isolation of the afflicted is meant to rouse the sick person to repentance. We might build upon the ideas of our teachers to suggest our goal is to remedy and repair, performing Tikkun upon “people,” “clothes,” and “houses” instead of tearing them down.

Afflicted people are those who are motivated solely by their own selfish considerations. The “clothes” represent the identities or communities with which we recognize our place in the society, the roles and responsibilities of our jobs that serve others or only ourselves. The “houses” are the institutions established to promote the common good, but have become corrupt perhaps undermining their missions, supporting very wrong they were intended to redress.

Judaism teaches us to care for the needy and weak. Clothing the naked, feeding the hungry, and caring for the widow and orphan is our charge. Our American tradition should measure our success by how well we care for the weakest among us. Freedom, liberty, and justice are our core values. They have made us a light to the nations. Our text gives us the opportunity to review what we do and consider course corrections to keep our sacred mission working. But the work begins with us.

Buber reflects that a person cannot find redemption until he/she recognizes the flaws in their own souls. A people likewise cannot be redeemed until it recognizes its flaw and attempts to efface them. Redemption comes only to the extent to which we can truly see ourselves. Redemption is not an act of grace; rather it comes when we make the world worthy of it. Only through our faith and deeds can we make so.

We are charged with a holy mission to be agents in the process of Tikkun and creation. We each are part of bigger things that begin with our own selves: family, country, and the world. How do we assume our responsibility in the work? It starts by living up to the standards to which we aspire, acting with kindness and respect for each other, and finding common ground to promote the common good; we must ensure our institutions embody our values, and actively support organizations that promote those values, here and in the world. Tazria/Metsora challenges us to act as though we are each a priest and to act embracing that each of us is B’tzelem Elohim, bringing the holy where it may not exist and effecting the changes we aspire to see in our lives.