In Judaism, it is pretty straightforward. We have a series of rituals and traditions that serve to guide us. But the answer is more nuanced depending in considerable measure on who you are and the relationship to the deceased.

Judaism compels us to “do the right thing.” It is one of our tradition’s great insights. Doing what we are supposed to do is affirming the bereaved’s humanity and sense of ethics. Even if the relationship was fraught, Judaism provides the ability to rise above circumstances instead of becoming a victim to circumstances.

Judaism compels us to “do the right thing.” It is one of our tradition’s great insights. Doing what we are supposed to do is affirming the bereaved’s humanity and sense of ethics. Even if the relationship was fraught, Judaism provides the ability to rise above circumstances instead of becoming a victim to circumstances.

In this week’s Torah portion, Chayei Sarah, we read that when Sarah died, Abraham wept (Genesis 23:2). But as is the case with Torah, there is more here than the words of the verse. The Torah has one of the letters of the Hebrew word for wept, livkotah, the kaf, printed physically smaller than the other letters. Our sages saw this as purposeful and concluded that this indicated that Abraham cried only a little. Why would Abraham not weep fully?

Perhaps he was overcome by guilt, bearing responsibility for her death. Midrashim tell of Sarah dying of a broken heart when she learns Abraham took their precious son Isaac and sacrificed to God on Mount Moriah. And to further compound things, Abraham knows in his heart that he would do the same thing again to prove his loyalty to God.

There are many reasons why we are unable to be fully present when we experience loss.

For example, Abraham negotiated for the burial cave and immediately focused on sending his servant to find a wife for Isaac. Most of us have experience with people focusing on funeral planning as a means of diversion from confronting the pain of loss. And many people experience complicated grief or ambivalence over the death of someone ostensibly close.

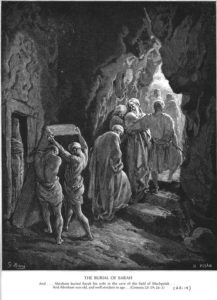

Our tradition offers us a roadmap of sorts when for the process of death and grief. My teacher Rabbi Dr. Michael Chernick wrote that we have obligations and responsibilities as the surviving loved one. Whether we loved them or even liked them, whether they were good to us or not, for our own sake, we need to do certain things on behalf of those who die. So we learned that despite Abraham’s weeping, or lack thereof, he purchased the cave at Machpelah and buried Sarah there.

As a rabbi, I am often asked how do I bury my loved one correctly? The fact that someone would ask means that, on some level, they already are. Together we can explore ways to help them.

But that is different from dictating what to do or how to feel. We have a framework. The task is to understand how our tradition can provide the honor of the deceased and comfort for the bereaved.

Recently, two adult children asked me to officiate the unveiling for their father. Then they changed their minds, cavalierly saying that as only a couple of prayers need to be spoken, they could do it without the expense of a rabbi in attendance. Besides, he (their father) never would have won father of the year.

As I listened, I knew that they would honor their father, but I also knew they were about to miss out on that crucial second piece of our tradition’s wisdom, finding their comfort. We spent some time talking as I was wearing my chaplain’s kippah. But I didn’t press. I hoped they might process the unveiling and the loss in a constructive way and bring them comfort and healing.

How do you process complicated grief? Abraham demonstrates that the question has been around for a long time. So may we find comfort in our memories of those deceased as we embrace the idea that they may be for us a blessing.